Background

Over the past while, there has been a national conversation on the tragic history of residential schools in Canada. The role of the Catholic Church in the residential school system has been a part of that discussion.

We acknowledge the terrible suffering that took place and condemn the system, established by the federal government and operated by faith communities, which separated children, often forcibly, from their parents and attempted to strip away their language, culture and identity.

The Catholic Church must atone for our involvement in this dark history. It is undeniable that some Catholic teachers (priests, religious men and women and lay staff) entrusted to care for children at residential schools assaulted the dignity of the students through mistreatment, neglect and abuse.

We echo the words of one of the original apologies made by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate in 1991:

“We apologize for the existence of the schools themselves, recognizing that the biggest abuse was not what happened in the schools, but that the schools themselves happened…We wish to apologize in a very particular way for the instances of physical and sexual abuse that occurred in those schools…Far from attempting to defend or rationalize these cases of abuse in any way, we wish to state publicly that we acknowledge they were inexcusable, intolerable and a betrayal of trust in one of its most serious forms. We deeply and very specifically, apologize to every victim of such abuse and we seek help in searching for means to bring about healing.”

Download PDF of this document: English or French

Frequently Asked Questions

- How many residential schools were there and where were they located? Did the Catholic Church run all these schools?

- What was the goal of residential schools?

- What were the causes of death for students at residential schools?

- I’ve heard a lot about the discovery of unmarked graves in British Columbia and Saskatchewan. How do I better understand these “lost” burial sites and those that may be present in other locations?

- Is the Archdiocese of Toronto and the Vatican holding records in secret archives. Why not just turn over all the information that you have?

- I have read many stories that talk about the Catholic Church not apologizing for their role in residential schools. Why hasn’t there been an apology?

- When was the delegation to Rome and who was part of it?

- Will the Catholic Church pay financial reparations to those harmed by residential schools?

- What is the Indigenous Reconciliaton Fund?

1. How many residential schools were there and where were they located? Did the Catholic Church run all these schools?

While the federal residential school system began around 1883, the origins of the residential school system can be traced to as early as the 1830s (long before Confederation in 1867), when the Anglican Church established a residential school in Brantford, Ont. It is estimated that 150,000 children between the ages of three and 16 were forced to attend federal residential schools, operated in Canada between 1883 and 1996.

Of the 139 residential schools identified in the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement (IRSSA), 46% (64 schools) were operated by Catholic entities; approximately 16 out of 70 Catholic dioceses in Canada were associated with the former residential schools, in addition to about three dozen Catholic religious communities.

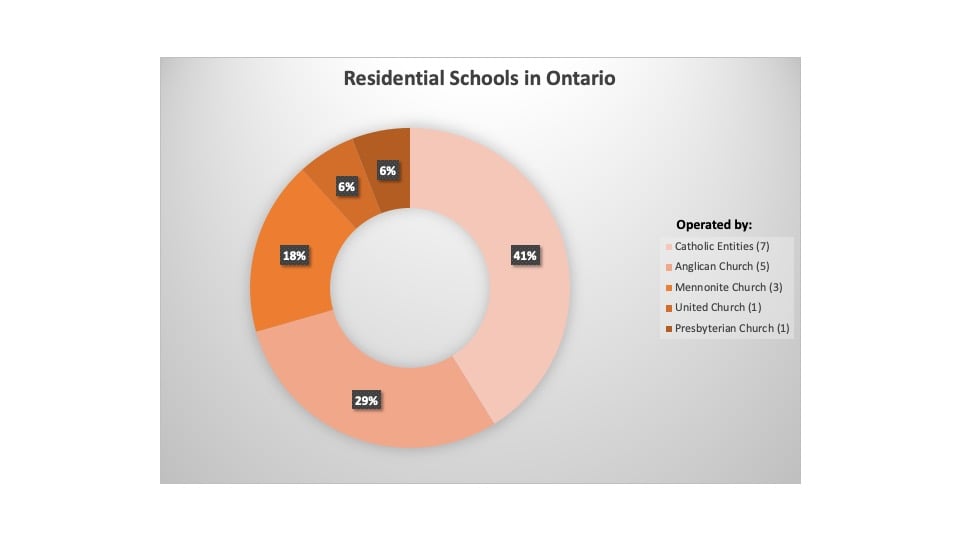

In Ontario, there were 17 residential schools:

- 7 were operated by Catholic entities,

- 5 by the Anglican Church,

- 3 by the Mennonite Church,

- 1 by the United Church and

- 1 by the Presbyterian Church.

No residential schools were operated in the Archdiocese of Toronto. The closest residential school was the Mohawk Institute in Brantford (1831-1970) operated by the Anglican Church.

Visit https://bit.ly/residentialschoolslocation to enter an address and find the closest residential school to your location. To view a map of residential school locations and religious affiliation click here.

2. What was the goal of residential schools?

Residential schools were established pursuant to federal government policies and legislation designed to control and assimilate Indigenous people. From the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Final Report:

For over a century, the central goals of Canada’s Aboriginal policy were to eliminate Aboriginal governments; ignore Aboriginal rights; terminate the Treaties; and, through a process of assimilation, cause Aboriginal peoples to cease to exist as distinct legal, social, cultural, religious, and racial entities in Canada. The establishment and operation of residential schools were a central element of this policy. The federal government’s residential schools were part of a horrendous assumption that it was in an Indigenous child's interest to be taken from his or her parents and to be culturally and linguistically reconstructed.

-

- The federal government never established an adequate set of standards and regulations to guarantee the health and safety of residential school students.

- The federal government never adequately enforced the minimal standards and regulations that it did establish.

- The failure to establish and enforce adequate regulations was largely a function of the government’s determination to keep residential school costs to a minimum.

- The failure to establish and enforce adequate standards, coupled with the failure to adequately fund the schools, resulted in unnecessarily high death rates at residential schools.

3. What were the causes of death for students at residential schools?

(Information below has been sourced from the Truth & Reconciliation Report – Volume 4 – Missing Children & Unmarked Burials)

- Approximately 150,000 children attended residential schools in Canada. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has identified 3,200 deaths on the Named and Unnamed registers of confirmed deaths of residential school students. Since the TRC report was published in 2015, the number of deceased children has most recently been updated to at least 4,100. Due to poor record keeping by the churches and the federal government, we may never know the total loss of life.

- For just under one-third (32%) of the 3,200 deaths identified in the TRC report, the government and the schools did not record the name of the student who died. For just under one-quarter of these deaths (23%), the government and the schools did not record the gender of the student who died. For just under one-half of these deaths (49%), the government and the schools did not record the cause of death. Aboriginal children in residential schools died at a far higher rate than school-aged children in the general population. (TRC Volume 4 – Missing Children & Unmarked Burials – Page 26-27)

- In cases where the cause of death was reported, tuberculosis was the dominant cause of death, representing 48.7% or 896 of residential school deaths. The next highest were influenza and pneumonia.

- Several of the schools were overwhelmed by the influenza pandemic of 1918–19. All but two of the children and all of the staff were stricken with influenza at the Fort St. James, British Columbia, school and the surrounding community in 1918. Seventy-eight people, including students, died. (TRC Report Summary, page 119)

- Underfed and malnourished students were particularly vulnerable to diseases such as tuberculosis and influenza (including the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918–19). In large part due to the federal government underfunding the system, food was low in quantity and poor in quality.

- Students also died as the result of suicide and accidents. Statistical analysis identified six suicides. The TRC report also identified 57 drownings, 40 deaths in school fires and 20 deaths due to exposure. 38 students died in a variety of other accidents, including vehicle accidents and falls. At least 33 students died while running away: they would have died from a variety of causes, the most common being exposure and drowning.

- According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report, parents frequently were not notified of a student’s death, and the bodies of students who died at residential schools were rarely sent home unless their parents could afford transportation. In an effort to limit expenses, the Department of Indian Affairs (as it was then called) was opposed to shipping the bodies of deceased children to their home communities.

4. I’ve heard a lot about the discovery of unmarked graves in British Columbia and Saskatchewan. How do I better understand these “lost” burial sites and those that may be present in other locations?

We can expect that there will be burial grounds on most, if not all, land in close proximity to residential schools. Ground penetrating radar has been used to identify individual graves. The technology does not identify human remains.

According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission: “Sometimes virtually no cemetery information is readily available within the archival records, but knowledge of the existence and location of cemeteries is locally held.”

Faith communities, including Catholic entities, who operated residential schools should have done more to respect those who died, providing information to family members and respecting the dignity of every child entrusted to their care. Church leaders have spoken publicly about the need to dialogue with Indigenous leaders to ensure appropriate memorials are constructed to remember and honour those who died, including names of the deceased wherever possible.

“We will offer to assist with technological and professional support to help the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc and other affected Nations in whatever way they choose to honour, retrieve and remember their deceased children.”

– Archbishop Michael Miller, Archdiocese of Vancouver – June 2021

Children were often interred with simple wooden crosses that have deteriorated and disappeared over the decades. At present, remains at the former residential school burial sites have not been identified. Local Indigenous leaders as well as historians have noted the need to identify the children buried on these sites. The school-related burial sites may also include the remains of lay teachers and their own children, as well as nuns, priests and other members of the community.

From the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report:

In the 1940’s, Indian Affairs was prepared to cover the burial costs of residential school students who died in hospital. It was not, however, prepared to pay for the transportation of the body to the student’s home community. The Social Welfare section of the 1958 Indian Affairs field manual provided direction on the burial of “destitute Indians.” Burial costs were to be covered by Indian Affairs only when they could not “be met from the estate of the deceased.” There was no fixed rate of payment.

Instead, the “amount payable by the local municipality for the burial of destitute non-Indians is the maximum generally allowed.” Those who died away from their home reserve were to be buried where they died. “Ordinarily the body will be returned to the reserve for burial only when transportation, embalming costs and all other expenses are borne by next of kin. Transportation may be authorized, however, in cases where the cost of burial on the reserve is sufficiently low to make transportation economically advantageous…

Given that schools were virtually all church-run in the early years of the system, Christian burial was the norm at most schools. Many of the early schools were part of larger, church mission centres that might include a church, a dwelling for the missionaries, a farm, possibly a sawmill and a cemetery.

The church was intended to serve as a place of worship for both residential school students and adults from the surrounding region. In the same way, the cemetery might serve as a place of burial for students who died at school, members of the local community, and the missionaries themselves.

For example, the cemetery at the Roman Catholic St. Mary’s Mission, near Mission, British Columbia, was intended originally for priests and nuns from the mission as well as for students from the residential school. Three Oblate bishops were buried there along with settlers, their descendants, and residential school students.

When the Battleford school closed in 1914, Principal E. Matheson reminded Indian Affairs that there was a school cemetery that contained the bodies of seventy to eighty individuals, most of whom were former students. He worried that unless the government took steps to care for the cemetery, it would be overrun by stray cattle. Matheson had good reason for wishing to see the cemetery maintained: several of his family members were buried there. These concerns proved prophetic, since the location of this cemetery is not recorded in the available historical documentation, and neither does it appear in an internet search of Battleford cemeteries.

From the Truth and Reconciliation Report

(Volume 4 – Missing Children pg. 118-119, 121)

The TRC report drew on the efforts of many investigators and consultants, including Dr. Scott Hamilton, a professor in the Department of Anthropology at Lakehead University, who worked from 2013-15 identifying residential-school-related gravesites across Canada.

His full, 44-page written report, “Where are the Children buried?” was made public only following Tk'emlups te Secwepemc Chief Rosanne Casimir’s announcement regarding the Kamloops discovery in late May 2021. In a recent interview with the B.C. Catholic, Hamilton said that he believes his study provides important detail and context for a public grappling with the implications of the Kamloops news. An excerpt from the B.C. Catholic story:

Of particular concern to Dr. Hamilton is the fact that many news reports described the Kamloops gravesite as a mass grave, a term most often used to describe sites associated with war crimes or massacres in which people all killed at one time are buried en masse in a site that is then hidden.

In fact, deaths at Residential Schools accrued year over year, with “wild fluctuations” that probably reflected periodic epidemics, Dr. Hamilton said. The high death rates continued until the middle of the 20th century, when they finally fell to match those in the general population.

Hamilton said the “mass grave” description “misses the point with the Residential-School story,” a story that unfolded over more than a century and in which appalling conditions led to high death rates due to disease, the most devastating of which was tuberculosis.

Deceased students were often buried in simple graveyards near the schools because federal authorities provided no funding to send the bodies home or to conduct proper burials…His report found no evidence that school officials intended to hide the graves. He also wrote that, in some areas, it is likely that the remains of teachers and their own children, nuns, and priests will also be found in school-related cemeteries. At present, none of the remains in Kamloops has been identified.

- Additional reading on this topic:

- The process for identifying unmarked graves (The National Post article – May 31, 2021)

- Where are the children buried? (Report of Dr. Scott Hamilton, professor in Anthropology who contributed to the TRC report)

5. Is the Archdiocese of Toronto and the Vatican holding records in secret archives. Why not just turn over all the information that you have?

“In the history of our Archdiocese of Keewatin-Le Pas, we had seven Residential Schools. We will do all we can to provide what information we have on our gravesites. During the TRC our records were turned over to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. We commit to help with identifying the children that passed at our own Residential Schools.”

– Archbishop Murray Chatlain – Keewatin-Le Pas – June 2021

-

Most Catholic entities that ran residential schools started sharing their records years ago. Cardinal Thomas Collins, along with other Canadian bishops, has stated publicly that any Catholic entity with records relating to residential schools that have not yet been shared should do so.

- No residential schools were operated within the boundaries of the Archdiocese of Toronto, so our diocese has no residential school records. The archdiocese holds no residential school records from other dioceses or Catholic entities.

- There is no evidence that secret files are hidden at the Vatican relating to residential schools. Records were kept by the religious orders and dioceses who ran the schools at the local level. Most groups have handed over records to the government or historical archives or committed to make this happen.

- Some records were lost over time. According to a 1933 federal government policy, school returns could be destroyed after five years and reports of accidents could be destroyed after ten years. Between 1936 and 1944, the federal government destroyed 200,000 Indian Affairs files (as the ministry was then called).

- Records of both the government and those that operated residential schools were inconsistent and often incomplete. Fires in a number of residential schools also damaged or destroyed historical records in some locations.

6. I have read many stories that talk about the Catholic Church not apologizing for their role in residential schools. Why hasn’t there been an apology?

Starting in the early 1990s, Catholic dioceses and religious orders that were directly involved in operating the federal government’s residential schools began issuing a series of apologies. These statements, along with an apology from the Canadian Bishops themselves, were included in a submission to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, which sat from 1991 to 1995. In addition to this, His Holiness Pope Francis issued several apologies in 2022 while meeting with Canadian representatives at the Vatican, and then again during his papal visit to Canada.

A brief timeline below:

|

1991 |

Apology by Catholic Bishops and Leaders of male and female religious communities: “We are sorry and deeply regret the pain, suffering and alienation that so many experienced. We have heard their cries of distress, feel their anguish and want to be part of the healing process.” – March 15, 1991 Other apologies from bishops and religious orders followed, to begin the path to reconciliation. You can read these apologies by visiting: www.cccb.ca/indigenous-peoples/indian-residential-schools-and-trc/ |

|

2006 |

Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) signed. The agreement (which went into effect in 2007) called for apologies from those responsible for operating residential schools. The desire was not only for an apology but a more important, ongoing journey to true reconciliation. |

|

2008 |

Then Prime Minister Stephen Harper made an apology in the House of Commons and announced the creation of the Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission. |

|

2009 |

Following a period of ongoing dialogue and a desire for a more direct connection to the Pope regarding residential schools, 40 Indigenous groups, led by the Assembly of First Nations, were received by Pope Benedict XVI at the Vatican. Media reports quoting Indigenous participants in the encounter with the Holy Father indicated that it was an appropriate response to the federal government’s apology along with those of other centrally organized churches (the United Church, Anglicans, etc.). One such example: CTV News – Pope apologizes for abuse at Indigenous schools - www.ctvnews.ca/pope-apologizes-for-abuse-at-native-schools-1.393911 Quotes from Indigenous and church leaders following the 2009 meeting with Pope Benedict XVI can be found here: www.cccb.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/2009_quotes.pdf “’We hoped to hear the Holy Father talk about the residential school experience, but also about abuses and hurts inflicted on so many and to acknowledge the role of the Catholic Church,’ [Chief Phil] Fontaine said in a news conference following the meeting. ‘We wanted to hear him say that he understands and that he is sorry and that he feels our suffering, and we heard that very clearly.’” |

|

2015 |

Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) re-examines the apologies from the Catholic Church. Without rejecting the 2009 process, it called for Pope Francis to come to Canada within a year to offer a Catholic apology in the name of the universal church. |

|

2017 |

Prime Minister Trudeau extends the request to Pope Francis on a visit to the Vatican. In the past St. John Paul II visited Canada on three occasions: in 1984, 1987 (joining Indigenous Peoples in a spiritual celebration in Fort Simpson, Northwest Territories) and for World Youth Day in 2002. |

|

2018 |

Pope Francis replied that he could not “personally” come to Canada at this time, as requested by the TRC. |

|

2019 |

In light of the understandable disappointment that a papal visit was not possible at the time, the Canadian bishops engaged in another process of consultation to arrange a second papal meeting with Indigenous survivors. Discussions commenced to arrange a delegation of Indigenous leaders, Elders and residential school survivors to meet with Pope Francis in Rome. The visit was to have taken place in 2020, but because of the pandemic, the timetable was delayed due to ongoing travel restrictions. |

|

2021 |

On June 6, Phil Fontaine, former Chief of the Assembly of the First Nations (AFN) who participated in the 2009 encounter with Pope Benedict XVI, spoke to the media and related that he felt an apology from Pope Francis was certainly possible and that activity was going on “behind the scenes.” A few days later, Perry Bellegarde, AFN National Chief, told the media that the meeting between survivors and Pope Francis was supposed to have taken place last year. "Many Catholic entities in dioceses across Canada have apologized publicly for their role in the operation of residential schools. What survivors and their families seek is something separate from these important acts…As we approach the 13th anniversary of the apology of the Government of Canada for the legacy of residential schools, we call on Pope Francis to deliver the apology that Indigenous peoples deserve." |

|

2022 |

While meeting with representatives of Indigenous communities from across Canada on April 1 at the Vatican, Pope Francis in his address stated: "I feel shame – sorrow and shame – for the role that a number of Catholics, particularly those with educational responsibilities, have had in all these things that wounded you, in the abuses you suffered and in the lack of respect shown for your identity, your culture and even your spiritual values. All these things are contrary to the Gospel of Jesus Christ. For the deplorable conduct of those members of the Catholic Church, I ask for God's forgiveness and I want to say to you with all my heart: I am very sorry. And I join my brothers, the Canadian bishops, in asking your pardon. Clearly, the content of the faith cannot be transmitted in a way contrary to the faith itself: Jesus taught us to welcome, love, serve and not judge; it is a frightening thing when, precisely in the name of the faith, counter-witness is rendered to the Gospel." In response to the apology by His Holiness, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau issued a statement that read in part: “Today’s apology is a step forward in acknowledging the truth of our past. We cannot separate the legacy of the residential school system from the institutions that created, maintained, and operated it, including the Government of Canada and the Catholic Church." |

|

2022 |

During Pope Francis' apostolic journey to Canada in July of 2022, His Holiness sought forgiveness on a number of different occassions. Excerpts of these apologies follow: "I have been waiting to come here and be with you! Here, from this place associated with painful memories, I would like to begin what I consider a pilgrimage, a penitential pilgrimage. I have come to your native lands to tell you in person of my sorrow, to implore God’s forgiveness, healing and reconciliation, to express my closeness and to pray with you and for you." - Pope Francis while meeting with Indigenous representatives of First Nations, Metis, and Inuit, July 25, 2022 in Maskwacis, AB "Today I am here, in this land that, along with its ancient memories, preserves the scars of still open wounds. I am here because the first step of my penitential pilgrimage among you is that of again asking forgiveness, of telling you once more that I am deeply sorry. Sorry for the ways in which, regrettably, many Christians supported the colonizing mentality of the powers that oppressed the indigenous peoples. I am sorry. I ask forgiveness, in particular, for the ways in which many members of the Church and of religious communities cooperated, not least through their indifference, in projects of cultural destruction and forced assimilation promoted by the governments of that time, which culminated in the system of residential schools." - Pope Francis while meeting with Indigenous representatives of First Nations, Metis, and Inuit, July 25, 2022 in Maskwacis, AB "I humbly beg forgiveness for the evil committed by so many Christians against the indigenous peoples." - Pope Francis while meeting with Indigenous representatives of First Nations, Metis, and Inuit, July 25, 2022 in Maskwacis, AB "I wanted to make this penitential pilgrimage, which I began this morning by recalling the wrong done to the indigenous peoples by many Christians and by asking with sorrow for forgiveness. It pains me to think that Catholics contributed to policies of assimilation and enfranchisement that inculcated a sense of inferiority, robbing communities and individuals of their cultural and spiritual identity, severing their roots and fostering prejudicial and discriminatory attitudes; and that this was also done in the name of an educational system that was supposedly Christian. Education must always start from respect and the promotion of talents already present in individuals." - Pope Francis while meeting with Indigenous peoples and members of the parish community of Sacred Heart, July 25 in Edmonton, AB "In that deplorable system, promoted by the governmental authorities of the time, which separated many children from their families, different local Catholic institutions had a part. For this reason, I express my deep shame and sorrow, and, together with the bishops of this country, I renew my request for forgiveness for the wrong done by so many Christians to the indigenous peoples. It is tragic when some believers, as happened in that period of history, conform themselves to the conventions of the world rather than to the Gospel. The Christian faith has played an essential role in shaping the highest ideals of Canada, characterized by the desire to build a better country for all its people. At the same time, it is necessary, in admitting our faults, to work together to accomplish a goal that I know all of you share: to promote the legitimate rights of the native populations and to favour processes of healing and reconciliation between them and the non-indigenous people of the country." - Pope Francis in meeting with civil authorities, representatives of Indigenous peoples and members of the diplomatic corps, July 27 in Citadelle de Quebec, QC "A short while ago, I listened to several of you, who were students of residential schools. I thank you for having had the courage to tell your stories and to share your great suffering, which I could not have imagined. This only renewed in me the indignation and shame that I have felt for months. Today too, in this place, I want to tell you how very sorry I am and to ask for forgiveness for the evil perpetrated by not a few Catholics who, in these schools, contributed to the policies of cultural assimilation and enfranchisement. Mamianak (I am sorry)." - Pope Francis in meeting with young people and Elders, July 29 in Iqaluit, NU |

|

2022 |

Catholic Bishops of Canada issue a statement of apology to the Indigenous People of This Land on September 24. In it, the Bishops acknowledged the suffering and abuses that took place in residential schools and expressed profound remorse as they apologized unequivocally. To read the entire statement, click here. |

7. When was the delegation to Rome and who was part of it?

On Tuesday, June 29, 2021, the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops announced the delegation will meet with the Holy Father in Rome from December 17-20, 2021.

“Pope Francis is deeply committed to hearing directly from Indigenous Peoples, expressing his heartfelt closeness, addressing the impact of colonization and the role of the Church in the residential school system, in the hopes of responding to the suffering of Indigenous Peoples and the ongoing effects of intergenerational trauma. The Bishops of Canada are deeply appreciative of the Holy Father’s spirit of openness in generously extending an invitation for personal encounters with each of the three distinct groups of delegates – First Nations, Métis and Inuit – as well as a final audience with all delegates together on 20 December 2021.”

Below is an excerpt from the June 10, 2021 statement from the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops:

This pastoral visit will include the participation of a diverse group of Elders/Knowledge Keepers, residential school survivors and youth from across the country. The event will likewise provide Pope Francis with a unique opportunity to hear directly from Indigenous Peoples, express his heartfelt closeness, address the impact of colonization and the implication of the Church in the residential schools, so as to respond to the suffering of Indigenous Peoples and the ongoing effects of intergenerational trauma.

8. Will the Catholic Church pay financial reparations to those harmed by residential schools?

The Catholic entities that operated residential schools were part of the 2006 Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement (IRSSA).

The 50 or so individual entities which signed the IRSSA previously paid:

- $29 million in cash (less legal costs);

- more than the required $25 million of “in-kind” contributions; and

- an additional $3.7 million from a “best efforts” campaign on a goal of $25 million. The Archdiocese of Toronto, and other Canadian dioceses, contributed through an in-pew collection held in December 2013.

In addition to payments made in the past, on September 27 of 2021, Canadian Bishops announced a pledge of $30-million over five years to support healing and reconciliation initiatives.

9. What is the Indigenous Reconciliation Fund (IRF)?

The Indigenous Reconciliation Fund, a national initiative, was established to accept donations from 73 Catholic entities across the country, and to advance healing and reconciliation initiatives, fulfilling the $30 million financial commitment made by Canada’s Bishops in September 2021.

The fund seeks to support projects that are determined locally, in collaboration with First Nations, Métis and Inuit partners. The Indigenous Reconciliation Fund has established the following criteria for grant applications:

- Healing and reconciliation for communities and families;

- Culture and language revitalization;

- Education and community building; and

- Dialogue for promoting indigenous spirituality and culture.

The fund has been designed to meet the highest standards of transparency and good governance and is overseen by a Board of Directors made up of Indigenous leaders. As of September 2024, the Indigenous Reconciliation Fund has raised $15,087,459.70 putting the fund on track for its five-year, $30 million commitment. To learn more about the IRF, visit their website at: www.irfund.ca

For complete details, please visit our page dedicated to the IRF.

Together We Pray

For the children who died in residential schools throughout Canada

and for all those who continue on a journey through the darkness,

that there may be healing founded on truth and that the Spirit

will inspire our ongoing commitment to reconciliation.

God, through the presence and power of the Holy Spirit,

continue to offer us correction so that your grace might change

and transform us in our weakness and repentance.

Give us humility to listen when others reveal how we have failed

and courage to love others as ourselves, mindful of your love

for the weakest and most vulnerable among us. Amen.

Also see:

- Our Lady of Guadalupe Circle

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada website – the site includes the full TRC report, Executive Summary, Calls to Action and numerous other reports and accounts from survivors.

- National Centre for Truth & Reconciliation (University of Manitoba)

- National Centre for Collaboration in Indigenous Education